ENGLISH

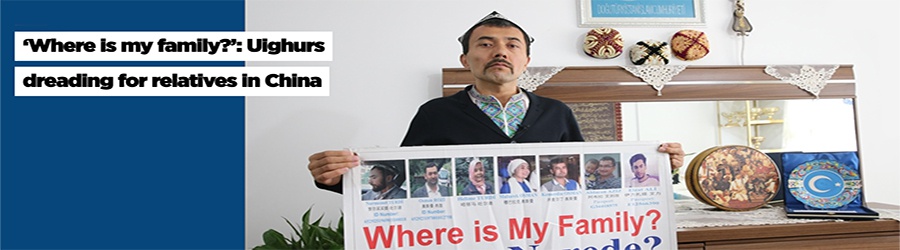

‘Where is my family?’: Uighurs dreading for relatives in China

Uighurs in Turkey want to find out about their relatives as Chinese authorities continue to take more Uighurs to controversial camps

It was a sunny summer day when Alimcan Turdiniyaz decided it was time to leave his homeland, where has lived all of his life, after he found out that his five-year-old daughter was arrested by Chinese authorities.

“My oldest daughter was only five-years-old when she was taken into custody by Chinese authorities in 2012 summer because she was attending a religious summer school,” he said.

He felt lucky as the family could get back the little girl from Chinese authorities with bribe. Turdiniyaz, 45, has been living in Istanbul for almost eight years with his three daughters and wife, but his heart is heavy with longing for his family and relatives back in the western Chinese region of Xinjiang, also known as East Turkestan.

The region is home to over 10 million Uighurs. The Turkic Muslim group, which makes up around 45% of Xinjiang’s population, has long accused Chinese authorities of cultural, religious and economic discrimination.

Nearly 100 people gathered peacefully outside the Chinese Consulate in Istanbul on Dec. 22, and protested for 18 days with a demand to know the well-being of their families, which they have never heard since 2017.

“My older brother, my older sister and her husband along with their two children, my other older sister’s son-in-law, as well a friend of mine are in China’s ‘so-called’ political re-education camps,” Turdiniyaz told Anadolu Agency in an exclusive interview.

He said Chinese authorities visited all Uighur families’ homes in Xinjiang in 2016 and they advised Uighurs to get passport and visit their families abroad.

“But little did we know it was a trap. Everyone who went abroad that year and onward are now in camps, or elsewhere which we do not know,” he said.

Clinging to tiny hope of seeing beloved on social media

Some are even recruited in Chinese factories for forced labor, according to Turdiniyaz. He said they check social media platforms such as TikTok and Facebook to see if they could have a “glimpse” of their families in video recordings.

“My older brother Nurmemet; he is educated and his own businesses are in China. He did not need the government to give him a job or education. But we later found out that he was taken due to his beard.”

Turdiniyaz’s sister Helime and brother-in-law Osman Rozi as well as their two children were taken to camps while his younger brother Elzat Ali is unaccounted for.

Working as a businessman in Turkey, Turdiniyaz was engaged in trade between China and Turkey until 2017.

“My younger brother Elzat was an accountant for my business from 2013 until 2017. In 2017, he returned home after we learnt that our mother was ill. As soon as he landed in China, he was taken in but we do not know whether he is in a camp or a prison, or elsewhere,” he said while bursting into tears.

Unable to hold back his moans, the heartsore man begged to find out about the condition of his families back in China.

“I cannot even call them because I do not want to put the remaining relatives of mine into trouble. I even found out the death of my own mother from others. I don’t know whether my brothers, my sisters or other relatives of mine are dead or live,” he sobbed.

Unable to communicate with families

A mother of two, Amine Vahit, 39, arrived in Turkey in March 2015 with her boys. Like Turdiniyaz, she was also importing and exporting goods to and from China until 2017.

Her world shattered when one morning she was unable to reach her family members. Using the popular China-based messaging app WeChat to communicate with her family, Vahit said she was no longer able to use it because everyone she knew removed the application from their phones and do not communicate with anyone abroad.

“I found out on July 2016 that my older brother was taken in by Chinese authorities, my sisters told me this through WeChat. But shortly after my older brother, my older sister and my other older brother were also taken in,” Vahit told Anadolu Agency.

Mentioning her last visit to her hometown Xinjiang, Vahit said her return to Turkey was an “absolute miracle.”

“I had to go because I had businesses there, and home that I wanted to sell but was unable to do,” she added.

Vahit’s sister was initially taken to camps in 2016 and had been held there for three months and then was released due to her deteriorating health condition.

“When I was down there, I secretly met my sister at the hospital. She told me to immediately leave the country before Chinese authorities took me in as well. So just like that I packed everything in one night and left with the first flight to Turkey,” she said.

Talking about camps, Vahit said her sister described them as a “nightmare” where women aged from 16 to over 70 were held.

“Every morning they were forced to run for an hour, including elderly women who were unable to even walk. Some lost their lives due to tough conditions in camps, according to my sister. A bun in the morning, a soup in the afternoon and another bun at night were given as food only in one condition.

“One could have to kneel down and thank the government of China and sign the Chinese communist party’s song to get that insufficient food,” she said.

Women in camps were treated poorly while they were forced to review their previous lives back at their hometown and “repent for it as if it was a sin,” according to Vahit.

Her sister was later taken to the camps in 2017 again, and since then Vahit does not know what has happened to her sister or her two brothers.

China has been widely accused of putting Uighurs into camps, and there have been reports of forced sterilization of Uighur women.

Beijing's policy in Xinjiang has drawn widespread criticism from rights groups including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, which accuse it of ostracizing 12 million Uighurs in China, most of whom are Muslims.

Mirzahmet Ilyasoglu, 39, has been living in Turkey since 2007 and became a Turkish citizen later on. Hoping to fulfil his late-father’s aspiration, Ilyasoglu received his university degree in China and got his postgraduate degree in Turkey.

Ilyasoglu invited his brother and mother to visit Turkey in 2014, where they visited touristic sights in Istanbul and saw a life beyond the unseen walls around Xinjiang.

But that travel turned out to be a nightmare for the Ilyasoglu family as his brother Helememet Ilyas was taken away by Chinese authorities in 2017 due to his travel to Turkey.

“We were told camps were occupational schools so I kept silent for three years. But when we did not hear from our families for three years, whether they were dead or alive, then we realized these were far from being schools,” Ilyasoglu said in tears.

‘Silence against oppression is a way of approving it’

He later found out that his brother-in-law Abdurrehman Kuerwanjiangin was also taken to camps along with Ilyasoglu’s four other friends.

Fighting to hold back his tears, he said: “I am not imprisoned but I feel just as they feel [referring to those in camps] … Through these camps, China is committing a crime. There is no other definition of this,” and burst into tears.

“Though the Chinese government always claims that the Xinjiang region is a part of China, it has never viewed the people located there as its own citizen,” he moaned.

Among those taken to China’s controversial camps, Ilyasoglu said, they know of relatives of their friends, who are elderly man aged 90 or above, as well as two-years-old children. Children are forcefully separated, Ilyasoglu said, citing information he received from the region.

Nearly 8 million people from the Muslim population in Xinjiang have been incarcerated in an expanding network of "political re-education" camps, according to Turdiniyaz.

“A friend of mine who had graduated from a university in Turkey died in those camps,” Ilyasoglu said while shaking in grief, and added that he fears for the life of his family members and friends.

Turdiniyaz, Vahit and Ilyasoglu all separately urged the international community, world countries and humanitarian organizations to speak up for the injustice and inhumane treatment by the Chinese government of the Turkic Muslim group.

“Silence against oppression is simply a way of approving it,” Ilyasoglu said.

Though Ilyasoglu welcomed the 2020 annual report of the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China (CECC), he said it was an overdue statement.

China has committed “crimes against humanity and possibly genocide” against the Uighurs and other Muslim minority communities in the western Xinjiang province, the recent CECC report said.

It added that “the Chinese government is intentionally working to destroy Uyghur and other minority families, culture, and religious adherence.”

In addition to new evidence of a systematic and widespread policy of forced sterilization and birth suppression of the Uighur and other minority populations, there is half a million middle and elementary school-age children, with many of whom involuntarily separated from their families, according to the CECC.

All of these trends “should be considered when determining whether the Chinese government is responsible for perpetrating atrocity crimes -- including genocide -- against Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and other Turkic and predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities in China,” the report read.

Living in Turkey since 2009, Medine Nazimi, 37, is also devastated, worried and fearing for her 34-years-old sister Mevlude Hilal.

Nazimi, who also gained her Turkish citizenship, said she does not know about her sister’s condition for over two years.

Hilal, who resided and studied in Turkey and holds a Turkish citizenship, was initially taken away by Chinese authorities in 2017 but released in 2019. Shortly after her release, she was forced to leave behind her then nearly two-years-old daughter and taken to camps in 2019.

Nazimi said they do not know since then whatever happened to her. Hilal’s daughter is now four-years-old and does not know her mother, nor she remembers her smell, the aunt said and burst into tears.

Nazimi lost her mother in 2019 shortly after her sister’s detention.

“How would you have felt if you had not spoken to your own mother for four years and then one day a phone rings and tells you she is dead now? And you could not even go to her funeral and pay your final tribute.”

Nazimi begged the Turkish government and the Foreign Ministry to find out about Hilal and bring her back along with her daughter to Turkey as they are citizens of the country.

“Consolations are no longer enough for us… We know many are either paralyzed or even died in those camps. All I want is to have my sister back in Turkey with her daughter. I want to be able to see my niece and hold her.”

“Though I live in a free country, I do not feel as if I am free. As days go on without knowing about my sister, I do not feel free,” she cried.

A 2018 Human Rights Watch report detailed a Chinese government campaign of “mass arbitrary detention, torture, forced political indoctrination, and mass surveillance of Xinjiang's Muslims.”

China, however, has repeatedly denied allegations it is operating detention camps in its northwestern autonomous region, claiming instead that they are “re-educating” Uighurs.

Türkiye delivered the 455,000th disaster housing unit to earthquake survivors

31 Arab, Muslim countries condemn Netanyahu's 'Greater Israel' goals

“Love in Scutari” Continues to Attract International Literary Attention

Geopolitical risks that began with Gaza genocide escalated by Israel’s regional attacks: Turkish president

Gaza death toll nears 61,400 amid Israel’s genocidal war

A Rise of Islamophobia in Canada

Turkish Technology Professionals from Around the World Meet on the TurkTechDiaspora Platform

Gaza death toll nears 53,300 as Israel continues its genocidal war

YTB sheds light on the Armenian issue in the shadow of historical sites

Police warn of 'distraction thefts' targeting Muslim community

Fired Microsoft employees accuse company of enabling Israel’s attacks on Gaza

Gaza death toll tops 51,100 as Israeli army kills 92 more Palestinians

Gaza death toll passes 50,500 mark amid ceaseless Israeli attacks

Islamophobia and anti-Palestinian racism in Canada higher than after 9/11, warns expert